The Curious Case of Hester’s Remains

Almost two centuries after her death, the enigma that was Lady Hester Stanhope continues to astonish and confound. Even the final resting place of her bones has a remarkable and bizarre twist…

Hester died in 1839 and despite her adamant desire to be given an Arab burial, she received her send-off wrapped up in the Union Jack, given a Church of England service fumbled together by the hapless priest who had galloped to her mountain fortress from Beirut with the equally hapless British consul. They had been aghast to find her dragoman and last lover Almaz had laid out her body in her Bedouin robes, her Druze’s ram’s staff next to a headless skeleton, with lit candles in the sockets of the skull, in her beautiful rose garden, all according to her instructions.

![]()

In August 1988, as the Lebanese civil war intensified, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in Whitehall received an unusual telex from Beirut concerning “the earthly remains of Lady Hester Stanhope.” The Red Cross had been contacted, then the British Embassy. A skull and human bones had been found “in the hills around Sidon.” Given that the region had been the scene of intense fighting for almost a decade, such a discovery hardly seemed unusual, but in this case, the remains were almost a hundred and fifty years old. It was said they belonged to a famous Englishwoman still well remembered in these parts, and with them was her ram’s head walking stick.

There was some confusion about how they had been found: Druze militiamen claimed that when they searched the hills around Joun, they came across a gravesite, already opened and desecrated. They blamed Shi’ite Amal militia, probably looking for treasure. But other reports suggested a local family may have opened the tomb. Then the news came that the skull had gone missing.

While the Western world watched as the drama of the Western hostages, among them the Archbishop of Canterbury’s envoy, Terry Waite and the journalist John McCarthy unfolded, the telex lines between the FCO’s Near East and North Africa Department (NENAD) and Beirut, also clattered with frenetic correspondence about Hester’s remains.

“We would be very grateful for any news about the fate of the Lady’s skull,” enquired one. “We have made various attempts to trace the whereabouts of Lady Hester Stanhope’s skull, so far without success,” replied another.

By the time incoming Ambassador Alan Ramsay had taken up the case, Mustapha Saad, the head of a Nasserite militia (one of the so-called “friendly militia” according to NENAD) was asked to retrieve what bones could be found “lying about the tomb,” so they could be “delivered to our West Beirut office.” The Guardian journalist, Julie Flint, had also managed to get up to the hill, where she too had found bones, gathered them in one place, and covered them with a layer of earth. The affair deepened when the Red Cross informed the embassy that the individual who had approached them with the offer to hand over “Lady Hester’s skull” and other remains seemed to be prevaricating. The Red Cross were leery of any financial transactions, meanwhile NENAD advised that it might not be desirable to “get into the position of bargaining for Lady Hester’s bones.” There was also the awkward business of trying to identify the remains: some of the bones were clearly masculine.

The fact that there appeared to be “other bones buried in the same grave” was an unexpected complication. In the end, the remains were handed over with no fee changing hands; the young man who secured them, Ali Hamoudi, was given a year of English language classes in Beirut as a reward. Her remains were loaded onto the back of a truck, to be shuttled through checkpoints of rival militia all the way up the country.

“For most of the past winter, Lady Hester’s remains have been storied in a grey cardboard box in my study. They consist of a few grey shards and some pieces of skull,” Ramsay informed Howe in March 1989. Ramsay broke the news that after a great deal of difficulty, due to “fighting in the Chouf area, [and] between the Hizbollah and Amal and on the other occasion because of an Israeli airborne attack on Palestinian positions nearby,” they had finally re-interred Hester in the garden of the British Embassy’s summer residence at Abey, a largely Druze village, still in the Chouf, overlooking Beirut. A ceremony was held on 2 February 1989, on “a beautifully clear, bright” day, to the sound of distant gunfire. She was re-interred in a rather inauspicious spot near the carpark, towards the side of the villa; guests would troop there, drinks in hand, at embassy parties. (Even the villa had not escaped drama: several years before it had been the scene of fighting between Druze militia and the Christian Phalange, and earlier had been occupied and looted by Israeli troops). Ramsay noted with some amusement, “She seems to have caused as much trouble posthumously as she did in life.” All the same, he “rather missed the sight of the grey cardboard box,” he said.

The Apparent End of The Matter:

On 23 June, 2004, 165 years after her death, Hester’s ashes were finally scattered across her garden in Joun. The residence at Abey had been sold, and the decision was reached by all parties – the British Ambassador James Watt, the Chevening Trust, and one of her distant descendants the Hon. William Stanhope and the Mayor of Joun, Roger Jawish – that she should stay in Lebanon. It was, after all, where she had chosen to be. The Stanhope crest, the British and Lebanese flags were raised in her honour.

But There’s More To The Story:

When I re-visited Lebanon and Syria in October 2010, I considered my subject long gone, no matter how dramatic the saga of her afterlife. But as I discovered, this was not quite the case…

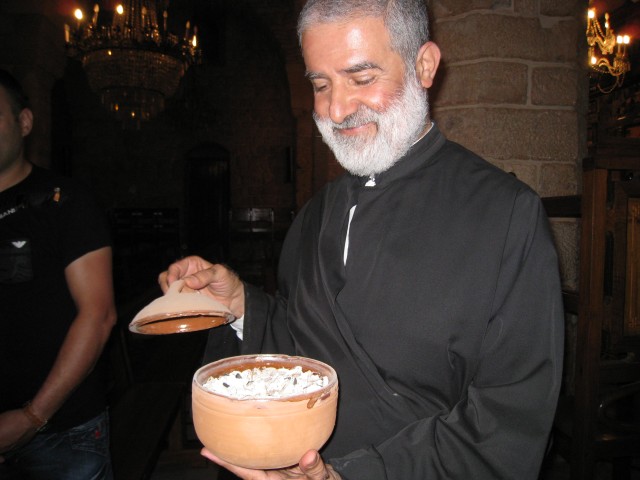

While making a pilgrimage once more to Hester’s ruined fortress at Joun, I revisted a friend I’d made on my earlier research trips, the Abbot of the nearby Melkite Monastery of Deir-el-Moukhalles. Over Arabic coffee and cakes, Father Sleiman revealed that he had personally been unable to bear the idea that such an important and illustrious personage as Hester – or Ul Uzza, Star of the Morning as she was called by the Arabs – should merely be scattered to the four winds. After the British delegates to her final funeral had departed, he sent his monks to gather up her remains. At the monastery, he told us, they revered and esteemed her for what she had done, all those years ago, as protectress of the local population and refugees when the Ottomans invaded in the 1830’s when she turned her fortress into a makeshift hospital and refuge. They gave her their highest mark of respect, to rest alongside their most honoured lineage of Bishops and Saints. Today they bless her week in the Melkite liturgy and bring out her remains for special occasions.

Would I like to see them. Or rather – gulp – her?

I like to think – indeed I would hazard to say, I believe – that Hester’s final wishes were to be buried with the body of the spy she loved, Vincent Yves Boutin, whose severed head and corpse she ordered to be given to her following his murder in 1815. If that were the case, then, as she intended in her will, Hester and her lost love were mingled for eternity.