Portraits of Hester

Hester once remarked to her doctor Charles Meryon that she intended never to have her portrait made. By then she was in her late 30’s. Yet she had numerous opportunities, at a time when having one’s portrait made was expected for a woman of her class. She was living with Pitt, for example, when he sat, numerous times, for the distinguished artist John Hoppner – I always found it intriguing to imagine what he might have made of her. I came to the conclusion that this claim of Hester’s – that she had deliberately refused to sit for a formal portrait and therefore commit an image of herself to posterity – did not necessarily include portraits for which she may well have posed, albeit fleetingly, in her youth, or those which she was not willing to acknowledge publicly. We can certainly suppose that the two reproduced in my book – Lady Stanhope as Hebe and the mysterious miniature assumed to be of Hester at Chevening – might fall into this category.

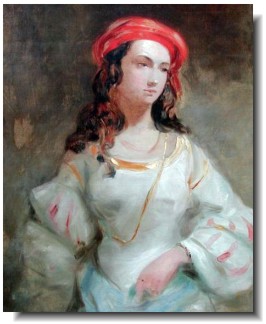

There are a number of portraits, of varied provenance, that purport to be of Hester. Here is one such portrait, which surfaced several years ago at the Olympia Fair. It has an unfinished quality, of a work swiftly drawn, apparently from life, costing its sitter no more than an hour or two of her time. Perhaps it was intended as a sketch for what be a more defined and elaborate finished portrait. It hints at her beauty, less so perhaps, at her character. The pose seems very traditional for a young girl of no more than 16 or 17: head tilted, eyes averted, gaze off to one side.

In my book’s illustrations, you can see a portrait of Hester Pitt, Hester’s mother, and if you compare the two, there does indeed seem to be a strong family resemblance, especially around the nose.

The portrait’s owners, Noel and Gwyennth James, bought it privately some 26 years ago from a large house Hungerford, West Berkshire. Noel James described how at the time he knew nothing about Lady Hester Stanhope, but was attracted to it “as a fabulous painting’ in its own right. Later, when the couple moved to Old Sarum – Thomas – ‘Diamond’ – Pitt’s famous old rotten borough, they became intrigued by the family connection, and decided it was too precious and intriguing to part with.

Details of the portrait are sketchy. The artist is unknown. The identification of the sitter is written in early typeface on the back of the portrait, estimated as ‘circa 1800.’ According to another old label, it was loaned for an exhibition at the South Kensington Museum by Mr C.Elphinstone Dalrymple of Aberdeen, in 18(?)6 bearing the title Lady Hester Stanhope.

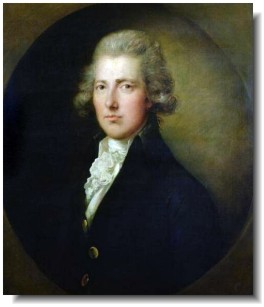

Gainsborough Dupont portrait of Pitt

Noel James had an unofficial appraisal by an art expert who speculated that it may be a late work by Gainsborough Dupont, Gainsborough’s nephew and assistant, which might date it therefore to the early 1790’s, which would certainly match the youthfulness of the subject. Gainsborough Dupont painted Hester’s uncle William Pitt and her relative Lord Wyndham Grenville, and other society figures, including Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire. If you look at Gainsborough Dupont’s portrait of Pitt, and again at this portrait there are indeed clues to consider, especially in the similarity in the treatment of the background.

But elements of this portrait, especially in its rendition of facial features and dress, brought to my mind the earlier work of Thomas Lawrence, who also painted a great many of Hester’s relatives and contemporaries, many of them leading politicians, including Pitt.

Among them were her friends and confidantes Sir Francis Burdett and George Canning. Lawrence also painted her lover, Granville Leveson Gower and the man she might have married, General Sir John Moore. Around the turn of the century, Lawrence made many portraits of Caroline of Brunswick, the Princess of Wales (and is generally assumed to have been one of her lovers. (Another was Hester’s cousin Sir Sidney Smith). This overlaps a time frame in which Hester found herself acting rather reluctantly as Princess Caroline’s lady-in-waiting at Blackheath so Lawrence may well have encountered Hester then.

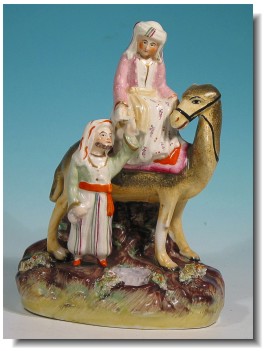

Staffordshire Hester

Imagined portraits of Hester form another category. There are the concocted versions of her in supposedly characteristic scenes by Robert Jacob Hamerton which were commissioned to illustrate Charles Meryon’s memoirs of Stanhope’s life and travels between 1840-45, producing a number of Victorian-era ‘Hesters’ – swathed in Orientalist robes and turbans, yet categorically not painted from life. Hester’s popularity as a Victorian talking point was given a final flourish in 1850 with the production by Thomas Parr of a set of Staffordshire porcelain figures, in which you can see a rather demure snowy-faced, apple-cheeked Hester, atop her camel, with the ever-constant Meryon, bringing up the rear.

Thanks to John Howard of Antique Pottery and Clarion Arts for the image of the porcelain Hester, and for more details, contact: Antique Pottery

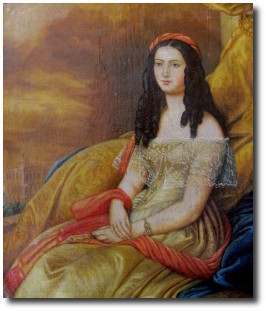

Lady Hester Stanhope in Malta

Intriguingly, two more portraits have surfaced, to be added to the pantheon of portraits reputedly of Lady Hester Stanhope.

The first, which is titled ‘Lady Hester Stanhope in Malta’, may have been painted from life, apparently shortly after Hester arrived in Malta where she and Michael Bruce stayed over the spring months of 1810 as guests of the island’s Governor, Major-General Sir Hildebrand Oakes. The artist is unknown, the picture, frame and style are typical of the early nineteenth century. Hester would then have been thirty-four. Now privately owned, it was purchased by auction in Malta.

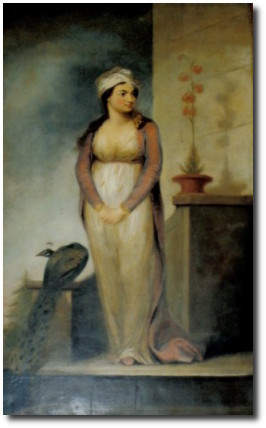

A Girl in Eastern Costume on a Terrace with a Peacock

The second, ‘A Girl in Eastern Costume on a Terrace with a Peacock’ by James Northcote RA (1746 – 1831) now hangs in the gallery at Stowe House, Buckingham, and over the years, and has always been regarded as being of Lady Hester, but whether painted from life or from the artist’s imaginative vision of her is not known.

Both portraits share several features which are consistent with the earlier portrait as well as ‘Lady Stanhope as Hebe,’ namely the very dark hair, worn loose and quite simply, the pale skin, rounded cheeks and arms, her very definite gaze and look of poised intensity.